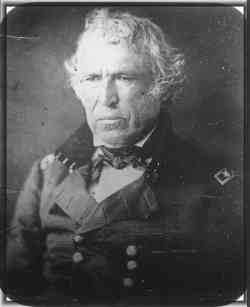

Zachary Taylor |

|

|---|---|

| Born | 11/24/1784 in Barboursville, Virginia |

| Died | 7/9/1850 in Washington, D.C. |

Biography |

|

Known as "Old Rough and Ready," Taylor had a forty-year military career in the United States Army, serving in the War of 1812, the Black Hawk War, and the Second Seminole War. He achieved fame leading American troops to victory in the Battle of Palo Alto and the Battle of Monterrey during the Mexican–American War. As president, Taylor angered many Southerners by taking a moderate stance on the issue of slavery. He urged settlers in New Mexico and California to bypass the territorial stage and draft constitutions for statehood, setting the stage for the Compromise of 1850. Taylor died of gastroenteritis just 16 months into his term and was succeeded by his Vice President, Millard Fillmore. Early lifeZachary Taylor was born on a farm on November 24, 1784, in Orange County, Virginia, to a prominent family of planters. He was the youngest of three sons in a family of nine children. His father, Richard Taylor, had served with George Washington during the American Revolution. Taylor was a descendent of William Brewster, one of the Pilgrims; James Madison was Taylor's second cousin, and Robert E. Lee was a kinsman. During his youth, he lived on the frontier in Louisville, Kentucky, residing in a small cabin in a wood during most of his childhood, before moving to a brick house as a result of his family's increased prosperity. He shared the house with seven brothers and sisters, and his father owned 10,000 acres, town lots in Louisville, and twenty-six slaves by 1800. Since there were no schools on the Kentucky frontier, Taylor had only a basic education growing up, provided by tutors his father hired from time to time. He was reportedly a poor student; his handwriting, spelling, and grammar were described as "crude and unrefined throughout his life." When Taylor was older, he wanted to join the military. Military careerZachary Taylor led the defense of Fort Harrison, near modern Terre Haute, Indiana.On May 3, 1808, Taylor joined the U.S. Army, receiving a commission as a first lieutenant of the Seventh Infantry Regiment from his cousin James Madison. He was ordered west into Indiana Territory, and was promoted to captain in November 1810. He assumed command of Fort Knox when the commandant fled, and maintained command until 1814. During the War of 1812, Taylor successfully defended Fort Harrison in Indiana Territory, from an attack by Indians under the command of Shawnee chief Tecumseh. As a result, Taylor was promoted to the temporary rank of major, and led the 7th Infantry in a campaign ending in the Battle of Wild Cat Creek. Taylor was also commander of the short-lived Fort Johnson (1814), the last toehold of the U.S. Army in the upper Mississippi River Valley until it was abandoned and Taylor's troops retreated to Fort Cap au Gris. Reduced to the rank of captain when the war ended in 1814, he resigned from the army, but reentered it after he was commissioned again as a major a year later. In 1819, he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel and was promoted to full colonel in 1832. Taylor led the 1st Infantry Regiment in the Black Hawk War of 1832, personally accepting the surrender of Chief Black Hawk. In 1837, he was directed to Florida, where he defeated the Seminole Indians on Christmas Day, and afterwards was promoted to brigadier general and given command of all American troops in Florida. He was made commander of the southern division of the United States Army in 1841. Mexican-American WarIn 1845, Texas became a U.S. state, and President James K. Polk directed Taylor to deploy into disputed territory on the Texas-Mexico border, under the order to defend the state against any attempts by Mexico to take it back after it had lost control by 1836. Taylor was given command of American troops on the Rio Grande, the Army of Occupation, on April 23, 1845. When some of Taylor's men were attacked by Mexican forces near the river, Polk told Congress in May 1846 that a war between Mexico and the United States had started by an act of the former. That same month, Taylor commanded American forces at the Battle of Palo Alto, using superior artillery to defeat the significantly larger Mexican opposition. In September, Taylor was able to inflict heavy casualties upon the Mexican defenders at the Battle of Monterrey. The city of Monterrey was considered "un-destroyable". He was criticized for not ensuring the Mexican army that surrendered at Monterrey disbanded. Afterwards, half of Taylor's army was ordered to join General Winfield Scott's soldiers as they besieged Veracruz. Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna discovered that Taylor had only 6,000 men, through a letter written by Scott to Taylor that had been intercepted by the Mexicans, many of whom were not regular army soldiers, and resolved to defeat him. Santa Anna attacked Taylor with 20,000 men at the Battle of Buena Vista in February 1847, inflicting 672 American casualties at a cost of 1,800 Mexican. As a result, Santa Anna left the field of battle. Buena Vista turned Taylor into a hero, and he was compared to George Washington and Andrew Jackson in the American popular press. Stories were reportedly told about "his informal dress, the tattered straw hat on his head, and the casual way he always sat on top of his beloved horse, "Old Whitey," while shots buzzed around his head". Election of 1848Taylor/Fillmore campaign posterIn his capacity as a career officer, Taylor had never reportedly revealed his political beliefs before 1848, nor voted before that time. He thought of himself as an independent, believing in a strong and sound banking system for the country, and thought that Andrew Jackson should not have allowed the Second Bank of the United States to collapse in 1836. He believed it was impractical to talk about expanding slavery into the western areas of the United States, as he concluded that neither cotton nor sugar (both were produced in great quantities as a result of slavery) could be easily grown there through a plantation economy. He was also a firm nationalist, and due to his experience of seeing many people die as a result of warfare, he believed that secession was not a good way to resolve national problems. Taylor, although he did not agree with their stand on protective tariffs and expensive internal improvements, aligned himself with Whig Party governing policies; the President should not be able to veto a law, unless that law was against the Constitution of the United States; that the office should not interfere with Congress, and that the power of collective decision-making, as well as the Cabinet, should be strong. After the American victory at Buena Vista, "Old Rough and Ready" political clubs were formed which supported Taylor for President, although no one knew for sure what his political beliefs were. Taylor declared, as the 1848 Whig Party convention approached, that he had always been a Whig in principle, but he did consider himself a Jeffersonian-Democrat. Many southerners believed that Taylor supported slavery, and its expansion into the new territory absorbed from Mexico, and some were angered when Taylor suggested that if he were elected President he would not veto the Wilmot Proviso, which proposed against such an expansion. This position did not enhance his support from activist antislavery elements in the Northern United States, as these wanted Taylor to speak out strongly against the Proviso. Most abolitionists did not support Taylor, since he was a slave-owner. Many southerners also held that Taylor supported states' rights, and was opposed to protective tariffs and government spending for internal improvements. The Whigs hoped that he put the federal union of the United States above all else. Taylor received the Whig nomination for President in 1848. Millard Fillmore of Cayuga County, New York was chosen as the Vice Presidential nominee. His homespun ways and his status as a war hero were political assets. Taylor defeated Lewis Cass, the Democratic candidate, and Martin Van Buren, the Free Soil candidate. Taylor was the last southerner to be elected president until Woodrow Wilson, as Andrew Johnson became president through succession. Taylor ignored the Whig platform, as historian Michael Holt explains: "Taylor was equally indifferent to programs Whigs had long considered vital. Publicly, he was artfully ambiguous, refusing to answer questions about his views on banking, the tariff, and internal improvements. Privately, he was more forthright. The idea of a national bank 'is dead, and will not be revived in my time.' In the future the tariff "will be increased only for revenue"; in other words, Whig hopes of restoring the protective tariff of 1842 were vain. There would never again be surplus federal funds from public land sales to distribute to the states, and internal improvements 'will go on in spite of presidential vetoes.' In a few words, that is, Taylor pronounced an epitaph for the entire Whig economic program." PresidencyPoliciesAlthough Taylor had subscribed to Whig principles of legislative leadership, he was not inclined to be a puppet of Whig leaders in Congress. He ran his administration in the same rule-of-thumb fashion with which he had fought Native Americans. Under Taylor's administration, the United States Department of the Interior was organized, although the legislation authorizing the Department had been approved on President Polk's last day in office. He appointed former Treasury Secretary Thomas Ewing the first Secretary of the Interior. SlaveryBy the time Taylor became President, the issue of slavery in the western territories of the United States had come to dominate American political discourse, and debate between extreme pro and antislavery viewpoints had become very pronounced. In 1849, he advised the residents of California, including the Mormons around Salt Lake, and the residents of New Mexico to create state constitutions and apply for statehood in December when Congress met. He correctly predicted that these constitutions would state against slavery in California and New Mexico. In December 1849, and January 1850, Taylor told Congress that it should allow them to become states, once their constitutions arrived in Washington D.C. He also urged that there should not be an attempt to develop territorial governments for the two future states, since that might increase tension between pro and antislavery activists regarding a congressional prohibition of slavery in the territories. Foreign affairsTaylor and his Secretary of State, John M. Clayton, lacked much experience in foreign affairs before Taylor assumed the presidency, and Taylor was not directly involved in diplomacy or the development of American foreign policies. Taylor's administration attempted to stop a filibustering expedition against Cuba, argued with France and Portugal over reparation disputes, and supported German liberals during the revolutions of 1848. The administration confronted Spain, which had arrested several Americans on the charge of piracy, and assisted the United Kingdom's search for a team of British explorers who had gotten lost in the Arctic. The United States had planned to construct a canal across Nicaragua, but the British opposed the idea, arguing that they held a special status in neighboring Honduras. In what was described by one source as Taylor's "most important foreign policy move", delicate negotiations were performed with Britain, and a "landmark agreement" was reached called the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty. Both Britain and the United States agreed not to claim control of any canal that might be built in Nicaragua. The treaty is considered to have been an important step in the development of an Anglo-American alliance, and "effectively weakened U.S. commitment to Manifest Destiny as a formal policy while recognizing the supremacy of U.S. interests in Central America". The creation of the treaty was Taylor's last act of state. The Compromise of 1850The slavery issue dominated Taylor's short term. Although he owned slaves on his plantation in Louisiana, he took a moderate stance on the territorial expansion of slavery, angering fellow Southerners. He told them that if necessary to enforce the laws, he personally would lead the Army. Persons "taken in rebellion against the Union, he would hang ... with less reluctance than he had hanged deserters and spies in Mexico." He never wavered. Henry Clay then proposed a complex Compromise of 1850. Taylor died as it was being debated. (The Clay version failed but another version did pass under the new president, Millard Fillmore.) DeathTaylor's mausoleum at Zachary Taylor National Cemetery.The true cause of Zachary Taylor's premature death is not fully established. On July 4, 1850, Taylor consumed a snack of milk and cherries at an Independence Day celebration. On this day, he also sampled several dishes presented to him by well-wishing citizens. Upon his sudden death on July 9, the cause was listed as gastroenteritis.[16] He was interred in the Public Vault of the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C. Later, he was interred in a mausoleum in Louisville, Kentucky, at what is now the Zachary Taylor National Cemetery. He was moved to his current mausoleum in 1926. In the late 1980s, Clara Rising theorized that Taylor was murdered by poison and was able to convince Taylor's closest living relative and the Coroner of Jefferson County, Kentucky, to order an exhumation. On June 17, 1991, Taylor's remains were exhumed and transported to the Office of the Kentucky Chief Medical Examiner, where radiological studies were conducted and samples of hair, fingernail and other tissues were removed. The remains were then returned to the cemetery and received appropriate honors at reinterment. He was reinterred in the same mausoleum he had been in since 1926. A monolith was constructed next to the mausoleum later on. Neutron activation analysis conducted at Oak Ridge National Laboratory revealed arsenic levels several hundred times lower than they would have been if Taylor had been poisoned.[17] Despite these findings, assassination theories have not been entirely put to rest. Michael Parenti devoted a chapter in his 1999 book History as Mystery to "The Strange Death of Zachary Taylor", speculating that Taylor was assassinated and that his autopsy was botched. It is suspected that Taylor was deliberately assassinated by arsenic poisoning from one of the citizen-provided dishes he sampled during the Independence Day celebration.[18] Rather, it was determined, as best it could be, that on a hot July day Taylor had attempted to cool himself with large amounts of cherries and iced milk. “In the unhealthy climate of Washington, with its open sewers and flies, Taylor came down with cholera morbus, or acute gastroenteritis as it is now called.” He might have recovered, Dr. Samuel Eliot Morison felt, but his doctors “drugged him with ipecac, calomel, opium and quinine (at 40 grains a whack), and bled and blistered him too. On July 9, he gave up the ghost.”[19] And most historians have adopted this viewpoint -- despite the facts that no eyewitness accounts have been offered to suggest that Taylor consumed cherries and milk on that day; that there is no proof of cholera in Washington in 1850; that Taylor's symptoms were not those of typhoid (spread by flies); that Taylor was not given the afore-mentioned drugs until he was already deathly sick, on the third day of his acute illness; and that Taylor was not bled until near death on the fifth and last day of his illness.[20] Unlike William Henry Harrison and the other six Presidents after him who died in office, Taylor was not elected in a year ending with a "0", making him an exception to the myth of Tecumseh's Curse. Personal lifeIn 1810 Taylor wed Margaret Smith, and they would have six children of whom the only son, Richard, would become a lieutenant general in the Confederate Army.[2] One of Taylor's daughters, Sarah Knox Taylor, decided to marry in 1835 Jefferson Davis, the future President of the Confederate States of America, who at that time was a lieutenant.[2] Taylor did not wish Sarah to marry him, and Taylor and Davis would not be reconciled until 1847 at the Battle of Buena Vista, where Davis distinguished himself as a colonel.[2] Sarah had died in 1835, three months into the marriage.[2] Another of Taylor's daughters, Margaret Anne, died of liver failure at age 33. Around 1841, Taylor established a home at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and gained a large plantation and a great number of slaves.[2] LegacyPresidential Coin of TaylorIt is contended that Taylor was not President long enough to cause a substantial impact on the office of the Presidency, or the United States, and that he is not remembered as a great President.[21] The majority of historians believe that Taylor was too nonpolitical, considering he was in office at a time when being involved in politics required close ties with political operatives.[21] The Clayton-Bulwer Treaty is "recognized as an important step in [the] scaling down [of] the nation's commitment to Manifest Destiny as a policy."[21] Taylor is one of only four presidents who did not have an opportunity to nominate a judge to serve on the Supreme Court. The other three presidents are William Henry Harrison, Andrew Johnson, and Jimmy Carter. In 1995, Taylor was inducted into the Louisiana Political Museum and Hall of Fame in Winnfield, Louisiana, the honor bestowed on the only U.S. President to have lived in Louisiana. Considering the shortness of his presidency, Taylor's most notable legacy may be that he was the last U.S. President to own slaves while holding the Office of the President of the United States, in 1850. |

|

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was the 12th President of the United States and an American military leader. Initally uninterested in politics, Taylor nonetheless ran as a Whig in the 1848 presidential election, defeating Lewis Cass and becoming the first president never to have held any previous elected office. He was the last Southerner elected president until Woodrow Wilson was elected 64 years later in 1912.

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was the 12th President of the United States and an American military leader. Initally uninterested in politics, Taylor nonetheless ran as a Whig in the 1848 presidential election, defeating Lewis Cass and becoming the first president never to have held any previous elected office. He was the last Southerner elected president until Woodrow Wilson was elected 64 years later in 1912.