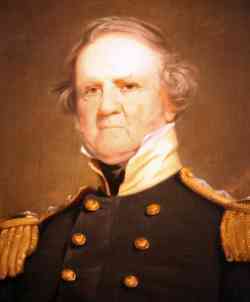

Winfield Scott |

|

|---|---|

| Born | 6/13/1786 in Dinwiddie County, Virginia |

| Died | 5/29/1866 in West Point, New York |

Biography |

|

A national hero after the Mexican-American War, he served as military governor of Mexico City. Such was his stature that, in 1852, the United States Whig Party passed over its own incumbent President of the United States, Millard Fillmore, to nominate Scott in the United States presidential election. Scott lost to Democrat Franklin Pierce in the general election, but remained a popular national figure, receiving a brevet promotion in 1856 to the rank of lieutenant general, becoming the first American since George Washington to hold that rank. Early yearsWinfield Scott was born on his family's plantation "Laurel Branch" in Dinwiddie County, near Petersburg, Virginia on June 13, 1786. He was educated at the College of William & Mary and was a lawyer and a Virginia militia cavalry corporal before being directly commissioned as captain in the artillery in 1808. Scott's early years in the United States Army were tumultuous. His commission was suspended for one year following a court-martial for insubordination in criticizing his commanding General, the pusillanimous and corrupt James Wilkinson. War of 1812During the War of 1812 in Canada, Lieutenant Colonel Scott took command of an American landing party during the Battle of Queenston Heights (Ontario, Canada) on October 13, 1812, but was forced to surrender, along with the militia commander Brigadier General William Wadsworth, when the majority of New York militia members refused to cross into Canada in support of the invasion. The next year, Scott was released in a prisoner exchange. Upon release, he returned to Washington to pressure the Senate to take punitive action against British prisoners of war in retaliation for the British executing thirteen American POWs of Irish extraction captured at Queenston Heights (the British considered them British subjects and traitors). The Senate wrote the bill after Scott's urging but President James Madison refused to enforce it, believing that the summary execution of prisoners of war to be unworthy of civilized nations. In May 1813, Scott (now a full colonel), planned and led the capture of Fort George on the Canadian side of the Niagara River. The operation, which used landings across the Niagara and on the Lake Ontario coast, forced the abandonment of the fort by the British. It was one of the most well-planned and executed operations of the war. In March 1814, Scott was brevetted brigadier general. In July 1814, Scott commanded the First Brigade of the American army in the Niagara campaign, winning the battle of Chippewa decisively. He was wounded during the bloody Battle of Lundy's Lane, along with the American commander, Major General Jacob Brown, and the British/Canadian commander, Lieutenant General Gordon Drummond. Scott's wounds from Lundy's Lane were so severe that he did not serve on active duty for the remainder of the war. A younger Winfield Scott.Scott earned the nickname of "Old Fuss and Feathers" for his insistence of military appearance and discipline in the United States Army, which consisted mostly of volunteers. In his own campaigns, General Scott preferred to use a core of U.S. Army regulars whenever possible. Scott perennially concerned himself with the welfare of his men, prompting an early quarrel with General Wilkinson over an unhealthy bivouac, which turned out to be on land Wilkinson owned. During an early outbreak of cholera at a post under his command, Scott himself was the only officer who stayed to nurse the stricken enlisted men. Nullification and the Trail of TearsIn the administration of President Andrew Jackson, Scott marshaled United States forces for use against the state of South Carolina in the Nullification Crisis. His tactful diplomacy and the use of his garrison in suppressing a major fire in Charleston did much to defuse the crisis. In 1832 Scott replaced John Wool as commander of Federal troops in the Cherokee Nation. Andrew Jackson disagreed with the United States Supreme Court views on the Cherokee right to self-rule. In 1835 Jackson convinced a minority group of Cherokee to sign the Treaty of New Echota. In 1838, following the orders of Jackson, Scott assumed command of the "Army of the Cherokee Nation", headquartered at Fort Cass and Fort Butler. President Martin Van Buren, who had been Jackson's Secretary of State, and then Vice President, thereafter directed Scott to forcibly move all those Cherokee who had not yet moved west in compliance with the treaty. Statue of Winfield Scott on Scott Circle in Washington, D.C..Scott arrived at New Echota, Cherokee Nation on April 6, 1838, and immediately divided the Nation into three military districts. He designated May 26 as the beginning date for the first phase of the removal. The first phase would involve the Cherokees in Georgia. He had to use militiamen (4,000 thousand of them) instead of regulars because the latter, though promised, had not arrived yet. Scott, however, preferred regulars, who, unlike the militiamen, did not stand to benefit from the removal (some militiamen, for example, had already laid claim to Cherokee properties); yet he had to work with what he was given. In a biography on Scott, Eisenhower notes how Scott was not an enthusiast for the removal of the Cherokees and even felt troubled about the justice of it. The moral implications of President Van Buren's policies (and of his predecessor, Andrew Jackson) did not make his orders easy. But as a public servant, not an elected official, he had to follow orders. All he could do was reassure the Cherokee people of proper treatment. In his instructions to the militiamen, he reminded them that any acts of harshness and cruelty would be "abhorrent to the generous sympathies of the whole American people" (many of whom, like John Quincy Adams, were against the removal, imputing it to "Southern politicians and land grabbers"). He also admonished his troops not to fire on any fugitives they might apprehend unless they should "make stand and resist." In addition, he got very detailed about helping the weak and infirm: "Horses or ponies should be used to carry Cherokees too sick or feeble to march. Also, "Infants, superannuated persons, lunatics, and women in a helpless condition with all, in the removal," deserve "pecular attention, which the brave and humane will seek to adopt to the necessities of the several cases." Scott's good intentions, however, didn't adequately protect the Cherokees from terrible abuses, especially at the hands of "lawless rabble that followed on the heels of the soldiers to loot and pillage." At the end of the first phase of the removal (August, 1838), 3,000 Cherokees had left Georgia and Tennessee by water to Oklahoma; but another 13,000 still remained in camps. Thanks to the intercession of John Ross in Washington, however,these Cherokees would travel, says Eisenhower, "under their own auspices, unarmed, and free of supervision by militiamen or regulars." Though white contractors, steamboat owners, and others who were profiting by providing food and services to the government protested, Scott did not hesitate to carry out this new policy (despite retired Andrew Jackson's demand [to the Attorney General] that Scott be replaced by another general and Ross be arrested). Within months he had every Cherokee in North Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama, who could not escape, captured or killed. The Cherokee were rounded up and held in rat-infested stockades with little food, according to some reports. Private John G. Burnett later wrote, "Future generations will read and condemn the act and I do hope posterity will remember that private soldiers like myself, and like the four Cherokees who were forced by General Scott to shoot an Indian Chief and his children, had to execute the orders of our superiors. We had no choice in the matter." Over 4,000 Cherokee men, women, and children died in this confinement before ever beginning the trip west. As the first groups that were herded west died in huge numbers in the heat, the Cherokees pleaded with Scott to postpone the second phase of the removal until after the summer, which he did. Determined to accompany them as an observer, Scott left Athens, Georgia, on October 1, 1838, and traveled with the first "company" of a thousand people, including both Cherokees and black slaves, as far as Nashville, where he was abruptly ordered to return to Washington to deal with troubles on the Canadian border. The Cherokee removal later became known as the Trail of Tears. On a new assignment, he helped defuse tensions between officials of the state of Maine and the British Canada province of New Brunswick in the undeclared and bloodless Aroostook War in March 1839. As a result of his success, Scott was appointed major general (then the highest rank in the United States Army) and general-in-chief in 1841, serving until 1861. During his time in the military, Scott also fought in the Black Hawk War, the Second Seminole War, and, briefly, the American Civil War. Scott as tacticianAfter the War of 1812, Scott translated several Napoleonic manuals into English. Upon direction of the War Department, Scott published Abstract of Infantry Tactics, Including Exercises and Manueuvres of Light-Infantry and Riflemen, for the Use of the Militia of the United States in 1830, for the use of the American militia.In 1840, Scott wrote Infantry Tactics, Or, Rules for the Exercise and Maneuvre of the United States Infantry. This three-volume work was the standard drill manual for the U.S. Army until William J. Hardee's Tactics were published in 1855. General Scott was very interested in the professional development of the cadets of the U.S. Military Academy. |

|

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786 – May 29, 1866) was a United States Army general, and unsuccessful presidential candidate of the Whig party in 1852. Known as "Old Fuss and Feathers" and the "Grand Old Man of the Army", he served on active duty as a general longer than any other man in American history and many historians rate him the ablest American commander of his time. Over the course of his fifty-year career, he commanded forces in the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, the Black Hawk War, the Second Seminole War, and, briefly, the American Civil War, conceiving the Union strategy known as the Anaconda Plan that would be used to defeat the Confederacy. He served as Commanding General of the United States Army for twenty years, longer than any other holder of the office.

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786 – May 29, 1866) was a United States Army general, and unsuccessful presidential candidate of the Whig party in 1852. Known as "Old Fuss and Feathers" and the "Grand Old Man of the Army", he served on active duty as a general longer than any other man in American history and many historians rate him the ablest American commander of his time. Over the course of his fifty-year career, he commanded forces in the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, the Black Hawk War, the Second Seminole War, and, briefly, the American Civil War, conceiving the Union strategy known as the Anaconda Plan that would be used to defeat the Confederacy. He served as Commanding General of the United States Army for twenty years, longer than any other holder of the office.